Meanwhile, the costs of producing goods overseas, and getting them here, are rising. Workers in places like China are demanding more, and oil prices make shipping costlier.

Experts say these trends are likely to continue.

Bank of America Merrill Lynch researcher John Inch wrote in a recent note to clients that the “U.S. economy is in the early stages of a long-term manufacturing renaissance.” Analysts at the Boston Consulting Group add that rising wages and other forces have steadily eroded China’s “once-overwhelming cost advantage as an export platform for North America.”

Thanks to higher U.S. worker productivity, as well as supply chain, cheap energy (natural gas) and logistical advantages, the BCG team says that by around 2015 “it may start to be more economical to manufacture many good in the U.S.”

In short, we could be on the cusp of revival of “Made in America,” with workers paid good wages for building things again. And for the millions in the army of the unemployed, it can’t come soon enough.

Silver lining to storm clouds?Don’t get me wrong. Our problems still run deep, and I’m not saying happy days are here again; I’m merely pointing out one of the few silver linings to be found.

We’ve long been too reliant on credit to supplement stagnant wages — and that’s left the West with an $8 trillion debt hole, according to Credit Suisse calculations. This fueled two bubbles and a financial crisis, and it resulted in the pitiful “recovery” we’re in now.

And so far, if the economy is reviving, most workers aren’t sharing in it. Real, inflation-adjusted wages have fallen in three of the past four months. This has never happened outside recession before. So it’s very possible we’re following Europe into the depths of a new downturn.

Last September, I argued that “the real recession never ended” and that, in reality, it started a decade or more ago as labor participation peaked in the late 1990s. We’ve been sliding lower ever since, trying to compensate for a lack of high-quality jobs and stagnant pay, with voodoo stimulus efforts out of Washington and an extreme, inflation-igniting easy-money policy from the Federal Reserve.

The core problem has been a hollowing-out of America’s manufacturing base because of increased globalization, the manipulative trade policies of China and others, and rapid technological change.

Washington, of course, hasn’t done anything about trade or jobs (except talk, of course). But the U.S. economy may find a way out of the hole anyway.

The depth of the problemBefore moving on, it’s worth remembering that something similar has happened before.

In many respects, the current situation resembles the Gilded Age of the late 1800s and the Long Depression, a global downturn that lasted from the 1870s through the 1890s. Replace the robber barons with hedge-fund managers and multinational CEOs, and the agitation over the Free Silver Movement with the Tea Party and the debate over the Federal Reserve’s stimulus efforts, and the similarities are striking.

The downturn was preceded by a period of global economic integration as steam power, the telegraph and railroads made the world smaller. Workers lost jobs to technology and foreign competition. The banking system was rocked by the panics of 1873, 1884 and 1893, driven by real-estate bubbles and stock speculation.

Our current role was played by the United Kingdom, an aging sovereign struggling to maintain its role as the world’s superpower. The role of the upstart United States is now played by vigorous up-and-comers like China and India. Check out this excerpt from A.E. Musson’s “The Great Depression in Britain, 1873-1896: A Reappraisal“:

“Britain was losing her technological lead; she was failing to modernize her plant, to develop new processes, or to modify her industrial structure with the same rapidity as Germany and the United States — owing to conservatism, the heavy cost of replacing old plant, and deficiencies in technical education.”

In other words, the British got lazy, making them vulnerable. We have the same problem now, and I outlined in “Are American workers getting lazy?”

The other part of today’s problem is that America’s free-trade policies put U.S. workers at a disadvantage, because trade partners aren’t playing fair. Beijing actively manages its currency’s exchange rate — accumulating trillions of dollars in reserves in the process — in an effort to ensure the country’s export-oriented growth isn’t threatened.

In this environment, research by the National Bureau of Economic Research shows that our economy will suffer if we don’t erect defensive trade barriers and tariffs.

Musson wrote that there was little doubt that a stagnation of British exports was “one of the most critical aspects” of the downturn and that aggression by trade partners was a primary cause. It’s the same for the United States today.

He writes: “Foreign trusts also adopted a vigorous policy of ‘pushing’ their goods abroad . . . while foreign industry and trade were greatly assisted by protective tariffs, export bounties, ‘drawbacks,’ and special low rates of rail transport. British business, on the other hand, had no such fiscal protection and assistance in this Free Trade era.”The result was a rise in calls for reciprocity and “fair trade.” It was argued that for Britain, as for the United States now, it would be ruinous to remain an open market when competitors were strongly protectionist. The result was a swing toward protectionism. Nothing much has been done on this front yet, but both presumptive GOP presidential candidate Mitt Romney and President Barack Obama have criticized China’s trade policies.

The tide is turningUnless the people rise up and demand change, I don’t believe the White House and Congress will do anything about our trade policies. Free trade and labor arbitrage have been very good for big business, pushing corporate profits

to record highs while average Americans struggle to fill their cars with gasoline.

Well-paid lobbyists will ensure that any anti-trade, anti-China legislation is dead on arrival to Congress. (Romney has promised to label China a currency manipulator, setting the stage for countervailing duties on Chinese goods. But legislation to do the same thing, which passed the Democratic-controlled Senate, has stalled in the Republican-controlled House.)

Fortunately, years of pain for American workers are bringing about a respite despite Washington’s recalcitrance.

The wage differentialConsider this: Back in 2000, in the twilight of the tech boom, factory wages in China averaged just 52 cents an hour — a mere 3% of what the average U.S. factory worker earned. In the years since, Chinese wages and benefits have jumped by double digits annually, with an average increase of 19% from 2005 to 2010.

With China’s workforce now peaking and labor shortages already developing in some of the coastal provinces, labor disputes and strikes — like the kind seen recently at factories supplying products as varied as flat-panel displays, auto parts and women’s lingerie — will surely become more common.

Beijing, mindful of the need to reorient China’s economy toward domestic consumption in the interests of sustainable growth, is becoming increasingly supportive of worker rights. Witness the recent regulatory spat over working conditions at Foxconn, the main supplier for Apple. Because of this, BCG anticipates further wage increases of 18% per year through 2015. By then, average pay in the Yangtze River Delta, the beating heart of China’s high-tech export machine, is expected to reach $6.31 per hour.

Here at home, fully loaded costs of U.S. production rose by less than 4% annually from 2005 to 2010 as labor unions became more flexible. Factoring in higher U.S. labor productivity, those Yangtze River Delta wages are likely to exceed 60% of U.S. manufacturing labor costs. After also factoring in favorable tax treatments for new factories, especially in Southern, nonunion U.S. states, the gap will be even smaller.

Plus, one must consider shipping expense, added wait times, and the plethora of hidden risks and costs of operating an extended global supply gain. China’s cost advantage won’t add up anymore.

Nor are other low-cost places like Vietnam and Indonesia suitable replacements, since they lack the infrastructure, talent, supply networks and productivity that have made China so attractive. For many, returning to the land of Stars and Stripes will be the best choice.

The impact on the economy will be “significant,” according to the BCG team. It identified seven industry groups — responsible for $200 billion in imports from China annually — for which rising costs in China will likely prompt the return of “Made in USA.” Examples include furniture, appliances, fabricated metals, machinery, transportation equipment, and plastics and rubber goods. Production of other items, such as apparel, textiles, footwear and computers, is expected to remain offshore.

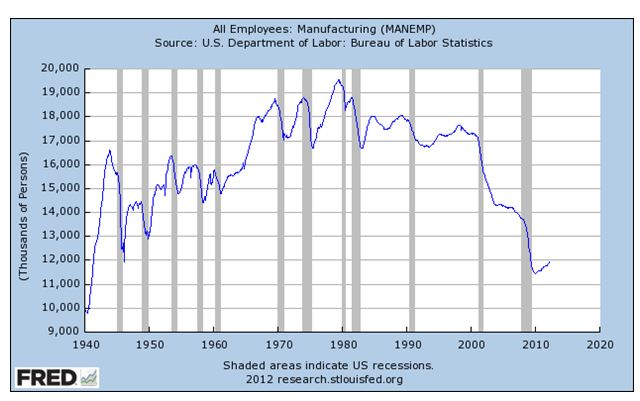

What will this mean? Take a look at the chart below, showing an uptick in manufacturing jobs after a long decline.

The Return of ‘Made in America’

The Return of ‘Made in America’